| WALKING ON THE MOON

Journey to The Lost World of Mount Roraima

| Ever since Walter

Raleigh described a mountain of crystal on his deluded

expedition up the Orinoco to find Lake Manoa and El Dorado,

the sandstone plateaux of the Guayana Shield have attracted

curiosity and conjecture, botanists and explorers, missionaries

and fortune hunters. |

Roraima

is the highest of the extraordinary mesa mountains that puncture

the plains of the ancient shield. Its flanks rise sheer above

the surrounding forests and savannahs, reaching 2,800 meters.

Its surface spans some 40 square kilometres, over six times

the size of Gibraltar. In the nineteenth century, reports

given at the Royal Geographic Society from this far-flung

corner of the Empire convinced many members that life on the

summit of Roraima, isolated from the world, could have been

suspended in its evolutionary development. Roraima

is the highest of the extraordinary mesa mountains that puncture

the plains of the ancient shield. Its flanks rise sheer above

the surrounding forests and savannahs, reaching 2,800 meters.

Its surface spans some 40 square kilometres, over six times

the size of Gibraltar. In the nineteenth century, reports

given at the Royal Geographic Society from this far-flung

corner of the Empire convinced many members that life on the

summit of Roraima, isolated from the world, could have been

suspended in its evolutionary development.

Speculation, at the height

of the great evolutionary debates in England, reached fever

pitch. In April 1877, only six years after the publication

of Descent of Man, an editorial in The Spectator pleaded "Will

no one explore Roraima and bring us back the tidings which

it has been waiting these thousands of years to give us?"

Various frustrated expeditions answered the call, but it took

until 1884 for the incongruous-sounding pair of Everard Im

Thurn and Harry Perkins, sponsored by the Royal Geographical

Society, the Royal Society and the British Association, to

bring back finally descriptions of its mysterious summit.

Im Thurn's account of his Jack and the Beanstalk adventure,

brimming with breathless conjunctions, is pure Boy's Own: Speculation, at the height

of the great evolutionary debates in England, reached fever

pitch. In April 1877, only six years after the publication

of Descent of Man, an editorial in The Spectator pleaded "Will

no one explore Roraima and bring us back the tidings which

it has been waiting these thousands of years to give us?"

Various frustrated expeditions answered the call, but it took

until 1884 for the incongruous-sounding pair of Everard Im

Thurn and Harry Perkins, sponsored by the Royal Geographical

Society, the Royal Society and the British Association, to

bring back finally descriptions of its mysterious summit.

Im Thurn's account of his Jack and the Beanstalk adventure,

brimming with breathless conjunctions, is pure Boy's Own:

"Up

this part of the slope we made our way with comparative ease

till we reached a point where one step more would bring our

eyes on a level with the top - and we should see what had

never been seen since the world began [...] should see that

of which all the few, white men or red, whose eyes have ever

rested on the mountain had declared would never be seen while

the world lasts - should learn what is on top of Roraima."

Sir

Arthur Conan Doyle drew on these vivid accounts to pen his

classic, if somewhat far-fetched The Lost World, published

in 1912, wherein the intrepid Professor Challenger encounters

pterodactyls and prehistoric cavemen running amok atop the

mountain. Two Hollywood films later, scientists are still

finding new species across the reach of these islands in time.

REVERENTIAL LOCALS AND PRESUMPTIOUS VISITORS

The

Pemon Indians that live in Roraima's shadow regard the 'tepuy'

('mountain' in their tongue) as the Source of All Waters,

home of the Goddess Kuín, grandmother of all Men. Its name

means 'large blue-green mountain.' The Pemon cherish and revere

Roraima. Richard Schomburgk, in his early Victorian expeditions

with his brother, noted "All their festive songs have

Roraima for subject matter, and when we told them of the beauties

of Pirara [...] their comment was and remained: 'It cannot

be nice in that place: there is no Roraima there.' "

In 1915, Mrs Cecil Clementi, wife of a diplomat posted in

Guiana, became the first woman to ascend the mountain. She,

like all visitors before or since, was spellbound. "We

felt smitten with awe and fear. We seemed so minute and presumptuous

to venture unbidden into the presence of these towering monsters

in a land that knew us not... Well may the Indians feel that

the place is holy ground!"

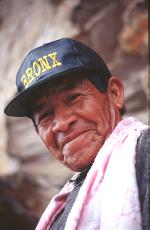

Even

though Julio, my sexagenarian Pemon guide, has climbed Roraima

more times than he has grandchildren (no less than twenty),

he still gets emotional about the mountain. Even

though Julio, my sexagenarian Pemon guide, has climbed Roraima

more times than he has grandchildren (no less than twenty),

he still gets emotional about the mountain.

"Look,"

he'd say, pointing to the mountain with no more than his protruding

lips, then pause, "beautiful."

Julio first climbed

Roraima in 1952, "when I was a youngster still,"

he chuckles. He guided the first expedition up the mountain's

twin, Kukenan. He spent three weeks looking for a way up.

Was

he ever scared?" I ask him.

"Maybe

the first time," he answers, "but then I would whisper

some taren (magical invocations), and always brought my machete

with me."

Julio's

present machete looks like it dates from another British expedition,

this time in 1964. On its blade, the words "Stainless

Steel" are still legible, but below them, only the upper

letters of "Birmingham" have survived decades of

diligent sharpening.

SERMONS IN STONE

We

spent our first night camped by the River Kukenan, close to

the villages where was villagers welcomed and fed Im Thurn.

The settlements have long since been abandoned, although one

can still make out the flattened earth circles where thatched

huts once stood. From this point, Roraima and Kukenan loomed

over the evening sky to the east and north-east, their sides

etched with white-line waterfalls.  Roraima's

south-western flank runs at a near right angle to Kukenan's

wall, forming an amphitheatre of rock into which unsuspecting

clouds drifted and dissipated. Only rarely do these "sermons

in stone" deign to reveal themselves fully. The rest

of the time they play hide and seek, skulking behind banks

of vapour. From here, Schomburgk "gazed in dumb amazement

at the mass of mountain with its sparkling bands of water

spreading itself out before me, until it became suddenly enveloped

in an envious veil of mist." Im Thurn's Indians never

tired of telling him that Roraima cloaked itself "whenever

approached by white men." With up to four metres of rainfall

a year in the area, the fabulous mountain lies, more often

than not, in the eye of the imagination. Roraima's

south-western flank runs at a near right angle to Kukenan's

wall, forming an amphitheatre of rock into which unsuspecting

clouds drifted and dissipated. Only rarely do these "sermons

in stone" deign to reveal themselves fully. The rest

of the time they play hide and seek, skulking behind banks

of vapour. From here, Schomburgk "gazed in dumb amazement

at the mass of mountain with its sparkling bands of water

spreading itself out before me, until it became suddenly enveloped

in an envious veil of mist." Im Thurn's Indians never

tired of telling him that Roraima cloaked itself "whenever

approached by white men." With up to four metres of rainfall

a year in the area, the fabulous mountain lies, more often

than not, in the eye of the imagination.

A

Marlborough and Oxford man, Im Thurn began his sojourn in

British Guiana as a magistrate in the Pomeroon district in

1882. There he lived for the next eight years on a low hill,

some 30 acres in extent, isolated from any other dry ground

by a great riverside swamp. Little wonder this "quiet,

unassuming chap" - as one Oxford contemporary described

him - would jump at the chance of attempting the ascent of

fabled Roraima. It took Im Thurn and Perkins, a Crown surveyor,

seven long weeks by foot and dugout to reach their camp on

the Kukenan from Georgetown.

BOTANICAL EL DORADO

The next day dawned cloudy

and misty - no bad thing for the tramp across the savannah

towards our shrouded goal. We climbed gently along the path,

occasionally negotiating sticky bogs imprinted, like a mud

logbook, with hundreds of trekking footsteps.

Only occasionally

did the ledge that cuts across Roraima's flank and up which

we would have to climb, appear, caught in brief snatches of

sunshine. Until Henry Whitely, an enthusiastic ornithologist

and orchid collector, first proposed this route as a means

of ascent, all previous expeditions had concluded that Roraima

was inaccessible. Barrington-Brown - the discoverer of Guyana's

Kaietur waterfalls - declared that a hot air balloon was required.

In 1878, Boddam-Wetham professed exasperated, "nothing

less than a winged Pegasus could expect to attain the summit

of the bare red wall that raised itself for hundreds and hundreds

of feet." As we reached the base camp at midday, the

rock fortress seemed all the more impregnable.

The

savannah around the base camp is rich in grasses, shrubs,

bracken and heath-like plants, but also numerous orchids,

including the yellows, whites and roses of Epidendrum on long

spindly stems. Here too, the pitcher plant Heliamphora thrives,

capturing insects in its sticky-bottomed tubular mouth. The

Schomburgk brothers were so impressed with the vegetation

they dubbed the skirts of Roraima a "botanical El Dorado."

In the forest above, dwarf compared to its low-lying counterparts,

the stunted trees and palms become thickly matted by swathes

of bamboo. As one climbs higher, green mosses wrap and muffle

everything - rock, trunk and branch - and all feels damp,

soggy and slippery.

The climb is as spectacular

as it is capricious, clambering up tripping roots, wood and

smoothed stone, round rocks and boulders, across boggy mulch,

between weaves of trunks, until emerging by a small brook

at the base of the cliff. Catching your breath, you look up

through a gap in the canopy. The vertical wall of rock thunders

up into the heavens, shooting down waterdrop arrows which

explode all around. Boddam-Whetham reached this point, but

found the way to the ledge blocked by insurmountable boulders.

Im Thurn wondered if he too would be forced to abandon the

ascent, his doubts exacerbated by the broken-up ledge, and,

more importantly, by the waterfall which vaulted down from

the summit at the far end of the ledge. The climb is as spectacular

as it is capricious, clambering up tripping roots, wood and

smoothed stone, round rocks and boulders, across boggy mulch,

between weaves of trunks, until emerging by a small brook

at the base of the cliff. Catching your breath, you look up

through a gap in the canopy. The vertical wall of rock thunders

up into the heavens, shooting down waterdrop arrows which

explode all around. Boddam-Whetham reached this point, but

found the way to the ledge blocked by insurmountable boulders.

Im Thurn wondered if he too would be forced to abandon the

ascent, his doubts exacerbated by the broken-up ledge, and,

more importantly, by the waterfall which vaulted down from

the summit at the far end of the ledge.

Having

spent the best part of a week cutting a trail through the

matted, soaked undergrowth, on December 18th he finally struck

out with his posse of Pomeroon and Pemon Arekuna porters.

Even now, after so many people have Grand-Old-Duke-of-York'd

up this mountain, it's hard going. But it's difficult to imagine

what unforgiving work slashing this trail for the first time

must have been like. In an expedition to the Guyanese north

face of Roraima in 1971, Adrian Warren's party cut a trail

along the mountain's upper slopes. They progressed only two

miles in six days. An assiduous amateur botanist, Im Thurn

was also collecting plant specimens as he went. Having

spent the best part of a week cutting a trail through the

matted, soaked undergrowth, on December 18th he finally struck

out with his posse of Pomeroon and Pemon Arekuna porters.

Even now, after so many people have Grand-Old-Duke-of-York'd

up this mountain, it's hard going. But it's difficult to imagine

what unforgiving work slashing this trail for the first time

must have been like. In an expedition to the Guyanese north

face of Roraima in 1971, Adrian Warren's party cut a trail

along the mountain's upper slopes. They progressed only two

miles in six days. An assiduous amateur botanist, Im Thurn

was also collecting plant specimens as he went.

As

we climbed higher, sweeps of cloud would reduce visibility

to a few yards. As quickly as they closed in, they disappeared.

When we finally emerged from the forest, the prospect below

resembled a conjured chessboard of forest and plain, sun and

rain - the Enchanter Light pondering his next move. From here,

we made our way down and round a giant boulder, before climbing

again towards the roar in the distance. The waterfall was

in full flow. Donning waterproofs for the first time, we hugged

the edge of the cliff and scurried as best we could over slimy

stone shingles under pounding waves of water.

STONE CLOUDS STONE CLOUDS

Beyond

the waterfall, the slope rises more steeply, effectively becoming

a gully between Roraima's dark, menacing ramparts. Picking

our way between hundreds of boulders, islands of numerous

ferns, Befaria heather and Heliamphora struggled, gradually

diminishing in size and number. Soon we'd come level with

the mythical summit of the mountain, enter, as Im Thurn put

it "some strange country of nightmares for which an appropriate

and wildly fantastic landscape had been formed, some dreadful

and stormy day, when, in their mid-career, the broken and

chaotic clouds had been stiffened, in a single instant, into

stone."

One small step onto a tepuy's

surface is one giant leap onto another planet. It's the Earth,

but not as we know it. Stygian amphitheatres of rock surround

you, carved over millennia by relentless rains and winds.

Faces and profiles, animals and hideous creatures, "apparent

caricatures of umbrellas, tortoises, churches, cannons and

of innumerable other incongruous and unexpected objects"

emerge in their strange, other-worldly shapes. The topography

dances in a funereal carnival of invention. Faint paths of

rubbed-away lighter rock provide the only bearings among the

ghostly, striated rock. Vegetation is sparse, reduced to weird

and wonderful plants, lichens and mosses. Water is everywhere,

running in rivulets, coursing through crags, gathering in

crystal-bottomed pools, faithfully seeking the mountain's

edge from which to hurl itself lemming-like. One small step onto a tepuy's

surface is one giant leap onto another planet. It's the Earth,

but not as we know it. Stygian amphitheatres of rock surround

you, carved over millennia by relentless rains and winds.

Faces and profiles, animals and hideous creatures, "apparent

caricatures of umbrellas, tortoises, churches, cannons and

of innumerable other incongruous and unexpected objects"

emerge in their strange, other-worldly shapes. The topography

dances in a funereal carnival of invention. Faint paths of

rubbed-away lighter rock provide the only bearings among the

ghostly, striated rock. Vegetation is sparse, reduced to weird

and wonderful plants, lichens and mosses. Water is everywhere,

running in rivulets, coursing through crags, gathering in

crystal-bottomed pools, faithfully seeking the mountain's

edge from which to hurl itself lemming-like.

Pagoda labyrinths, valleys

of crystals, dark chasms and inky sinkholes that disappear

in the depths punctuate Roraima's moonscape surface. Star-shaped,

Catherine wheel flowers on long spiny stems, carpets of fluorescent

green moss, spiky yellow-orb flowers and carnivorous pitcher

plants cling to nooks and crannies, sparkling in the rare

moments of blinding sun. Stunted Bonnetia trees with wide

boughs and spindly leaves recall Japanese Zen gardens, the

primeval soup landscape washed over by Hokusai waves of brush-stroke

clouds. Pagoda labyrinths, valleys

of crystals, dark chasms and inky sinkholes that disappear

in the depths punctuate Roraima's moonscape surface. Star-shaped,

Catherine wheel flowers on long spiny stems, carpets of fluorescent

green moss, spiky yellow-orb flowers and carnivorous pitcher

plants cling to nooks and crannies, sparkling in the rare

moments of blinding sun. Stunted Bonnetia trees with wide

boughs and spindly leaves recall Japanese Zen gardens, the

primeval soup landscape washed over by Hokusai waves of brush-stroke

clouds.

The odd bird flits and chatters, but otherwise, the

silence is deafening. Unerring. You lose all sense of scale,

any track of time. The land is old - these were once the valleys

of Gondwana and Pangea, brimming with gold and diamonds, charged

with Life's current for over two billion years. The landscape

is in constant motion. Fluid. Yet completely static - like

a giant cog in the wheel of time, slowly clunking the gears

of evolution, it has witnessed every wonder of Nature, and

every folly of Man.

HYDROLOGY MADE EASY

To the north of its surface,

the borders of Venezuela, Guyana and Brazil meet. Roraima

divides their respective watersheds: the Orinoco, Essequibo

and Amazon. Roraima is more than a mountain. In few parts

of the planet are the elements more present. The Guayana Shield's

water cycle, from tepuy to forest to sea and back again, resembles

"Chapter 2: Hydrology" in a 14-year old's Geography

textbook. To the north of its surface,

the borders of Venezuela, Guyana and Brazil meet. Roraima

divides their respective watersheds: the Orinoco, Essequibo

and Amazon. Roraima is more than a mountain. In few parts

of the planet are the elements more present. The Guayana Shield's

water cycle, from tepuy to forest to sea and back again, resembles

"Chapter 2: Hydrology" in a 14-year old's Geography

textbook.

Venezuela's

Canaima National Park, the world's sixth largest park which

protects Roraima, fulfilled all five criteria for inclusion

as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The waterfalls which spring

from the tepuys - including the world's tallest, Angel Falls

- weave together to form the fishhook arc of the River Caroní,

which in turn disgorges into the mighty Orinoco. Where the

two rivers meet, the Guri Dam furnishes some 70% of the country's

electricity. As much as 40% of the tepuys' species are entirely

endemic, their evolution isolated for millennia. Of the park's

five frogs in the Oreophrynella order, each claims its very

own tepuy.

Although creatures little larger than thumbs are

hardly the stuff of science fiction yarns, regional expert

and guide Roberto Marrero has published a map detailing

UFO phenomena across the national park. The tepuy's profile

make the most Spielbergesque landing site you could possibly

encounter.

I ask Julio about his experiences,

eager for stories of strange beasts. The only animals he's

spotted, in turns out, are the foxes and dogs that come to

scavenge the visitors' food.

PARTING LOOKS

Roraima makes an inhospitable

host. The summit is cold and damp; clothes never dry; you never shake the feeling you shouldn't be present in this

re-animated Dürer engraving at all. The rock's eerie, Wagnerian

forms begin to seep under your skin. After three nights, you're

ready to come down.

As

soon as we began our descent, banks of clouds drew in around

us, and Roraima's drawbridge clanked shut. Nearing the Kukenan

river on our way back, the mountains slowly began to emerge.

We struggled across the river, its hungry waters lapping at

our waists and rucksacks. On the far bank, Julio called me,

nodding his head back towards Roraima. I turned to see the

mountain's walls glowing blood red, serene in the still evening

air. "Parting looks," says the old Welsh proverb,

"are magnifiers of beauty."

A

paragon of modesty, Im Thurn insisted the conquering of Roraima

amounted to no more than "a long walk ending in a successful

scramble" according to R.R. Marrett. I think he was being

bashful. Climbing Roraima, then and now, is a journey to a

unique lost world.

FOR TOURS OF RORAIMA, CONTACT

For

more on the Gran Sabana and Canaima National Park, see

|